|

What is a fasting

girl?

Fasting

Girls were girls or women in the Middle Ages who

were said to eat little or nothing and yet live. These

girls were also sometimes said not to

defecate or sweat or menstruate. This

was thought of as miraculous as well as curious, and these women and

girls drew

a lot of attention from regular people and the church. People

came to see them, give them money,

learn what God had revealed to them (if anything), and basically

treated them

as if they were holy, if curious, persons.

Dorothy of Montau (b.

1347), her image at the center of this shrine, began practicing severe

fasting even as a

child. As a woman she lived as a hermit

and fasted to the point where she stopped defecating.

When taking communion, she fell into fits of

ecstasy. (Photo from Wikipedia, by Marcin

N, 2006, creative commons sharealike license.)

The term ‘fasting girl’

may have been popularized by the

political pamphlet writers in England

during the English Reformation, when King Henry VIII separated England

from the Catholic church and created the Church of England.

What is fasting?

Fasting

has long been an activity of those of all faiths who

seek spiritual health and connection. Fasting at its most basic simply

means that

a person does not eat certain foods. Today,

we often associate fasting with a toxin cleanse, such as the grapefruit

diet. But long ago (and still today),

fasting was primarily about spiritual

health. People avoided foods that they

felt kept them

from communion with God.

Fasting in medieval

and early Christianity:

Medieval

Catholics practiced extensive fasting. Throughout

the middle ages in the West, the

week was divided into “lean days” and “meat days.” On

lean days (which were 'fast days'), you could eat fish, birds,

eel, or even beaver tail (which was

considered ‘fish’), and drink almond milk. Meat or milk from four

legged

creatures, including butter and cheese, could be eaten only on meat

days. If you ate meat on a lean day, you had to go to confession

and confess it.

Where

does this meat vs fish thing come from? Many

cultures have dietary restrictions as

part of their religious expression. But

Christian ‘lean day’ fasting probably came in part from the ancient

Greeks who

applied their philosophies of ‘world vs spirit’ to early Christian

theology and

practice. The idea was that lean day foods

were more spiritual and less corrupted by the world than were the meat

day

foods. Food of and from the air and

water, like fish and birds, was ‘purer,’ or higher up on the spiritual

ladder, than

food that came from goats, sheep, or cows.

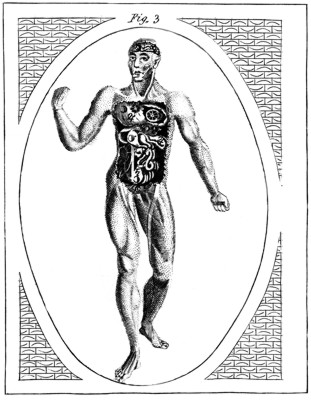

In this

illustration, we see ‘Man.’ Originally created with God-like power, he

is now corrupted by the fall of Adam and

Eve, a fall that took him from the spirit/God realm to the corrupt

world of

flesh. ‘Man’ is now contaminated by sin

and flesh and earth, and is susceptible to corruption and disease. (Illustration from Ebenezer Sibly, 1806,

posted

on fromoldbooks.org.)

Early

Greco-Roman Christians may have inherited the idea of

dietary restrictions for religious reasons from the Hebrews, but they

applied

it in a very Greco-Roman way. Regardless,

fasting became a predominant form of

religious expression in Christianity. Fasting

was associated with Godliness and miracles. Those

who engaged in fasting as a rigorous

practice could be said to be creating or expressing a ‘hunger for God’

that at

times became ecstatic or overwhelming. Fasting,

could be, and sometimes was, practiced to the

extreme.

Spiritual athletes:

Early

devout Christians flocked to the desert and lived in

little cells or caves or single room dwellings. (See

my article What

is an Anchorite?) Desert monks and

hermits (both men and women) prided

themselves on their

ability to abstain from food. That these

men and women could live without seeming to eat anything showed their

spiritual

vigor. Some claimed they did not eat

food at all. (See the interesting modern case of Prahlad Jani

) There are also many stories about monks pretending to eat for

appearances

sake, while instead hiding the food in their sleeves or under cloths

and later

giving that food to someone else.

People

who lived when they did not eat (or ate very

little) were thought to live by their spiritual strength (or by

spiritual

intervention) alone. Some of these desert men and women relate

instances where

they consumed spiritual food delivered to them by angels.

They believed that in their extreme fasting

and other practices, that they were leaving suffering and the world

behind them. They hoped that through

prayer and meditation

and endurance, they could escape the “corruption” of Man on earth and

live by

spirit alone. In their feats of

endurance, suffering, starvation and hardship, they were called

spiritual

athletes, and they often drew crowds of admirers to see them and

consult with them.

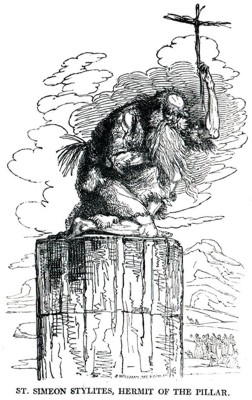

The Syrian Saint Simon (Symeon) was

one such spiritual athlete. He lived for

more than 30 years on a small platform on top of a pole. Theodoret

of Cyrrhus tells us: “ Night and day he is standing within the view of

all…now

standing for a long time, and now bending down repeatedly and offering

worship

to God….In bending down he always makes his forehead touch his toes—for

his

stomach’s receiving food once a week, and little of it, enables his

back to

bend easily…”

(Theodoret quoted by William

Harmless, Desert Christians, 2004, page 465. Image from Hone's Everyday

Book, 1826, posted on fromoldbooks.org)

The

Desert men and women became the monks (a Greek word) and

nuns of the middle ages. These spiritual

athletes (also called ‘aesthetics’ who practiced aestheticism) were

discouraged

by church and government. Too many

people communing so directly with God was disruptive and chaotic. Additionally, people like St. Benedict

recognized that such practices were far too extreme to be healthy, and

he

encouraged his followers to be more moderate. Still,

however, Benedict continued to advocate regular fasting.

Many of

the saints of the Middle Ages practiced at least

some kind of fasting. Though the church

discouraged extremes, spiritual athletes persisted, popping up in the

middle

ages as both religious monks and nuns and lay men and women. They often earned a good deal of admiration

and respect from those around them and their reputations could be

widespread. People thought their ability to

ignore their

own suffering (to deny the body) proved them to be spiritually strong

or blessed

and so closer to God. Or, if fasting did

not seem to bring them suffering, they were admired for their

miraculous

ability to not eat and yet not

to suffer.

Women saints who

fasted:

In the

medieval period, the importance of care of the soul

far outweighed the importance of care of the body. Today

we spend a great deal of time and

energy caring for our bodies, exercising, outfitting, and botoxing them. We have a hard time understanding, then, how

historically

it was care of the soul that was of vital importance, even if that

meant

suffering for the body. (See my article

on Medieval

Hospitals.)

In the

medieval context, fasting becomes an expression of

the soul over and above the needs of the body. The

spiritual soul manifested through the body in a number of different

ways. Fasting was only one manifestation of extreme aestheticism. Women and girls were also known to have

stigmata, to levitate, to leak or ooze bodily or mysterious fluids, to

disfigure

their bodies or otherwise attempt to render themselves unattractive,

shut

themselves away in small cells, and be swept into fits of hysteria when

receiving the Eucharist (or when thinking of the Eucharist). A number of them claimed the only ‘meal’ they

ate was the Eucharist itself. (Eucharist is also called Communion, it

is the Christian ceremony that distributes bread as the body--usually

only a small wafer--and wine as the blood of Christ.)

Saint Lidwina of Schiedam

(b. 1380) tried to disfigure her pretty face. Later

she suffered an accident that lead to a

gangrenous disease that

caused pieces of her body to fall off. She

is said to have been able to taste the difference between bread that

had been

consecrated to God, and bread that had not. (Image from a woodcut, from

wikipedia commons.)

Some of these fasting women

sought to escape marriage, or were

dealing with other issues of suffering in their lives that seemed to

manifest

in extreme behaviors. Perhaps their

often extreme focus on receiving the Eucharist as an actual (and only)

meal

came from some inner compulsion to deal with the troubles of their

lives. Regardless, these women were both feared

and

admired.

Women

such as Joan the Meatless could be simultaneously threatening

to the power structures of the church, and good for promoting miracles

and the

worship of saints. The church, therefore, put a lot of effort into both

containing these women and girls, and chronicling their exploits. Those women who became saints, such as in the

case of Christina the Astonishing, were often made the patronesses of

the very

things they seemed to suffer from most in their attempt to imitate the

sufferings of

Christ. Christina the Astonishing is the patron saint of insanity,

mental disorders, madness, lunatics, and mental health

providers.

Feasting on

spiritual food:

Visions

and fits of ecstasy were common in women who

fasted. Their visions were often

recorded and circulated by priests who served as their confessors. Both lay women (ordinary Christian women, not nuns)

as

well as religious women could express their faith through fasting and

ecstatic

fits.

In the

cases of religious women, where it is the Eucharist

itself triggers the fits, it seemed clear that such ecstasies must have

come

from God. But things could be more

difficult for lay women, as sometimes these fits were considered

annoying to

one’s neighbors. Certainly this was true

in the case of the fit-throwing Margery Kempe, who regularly disrupted

church

services by throwing herself into the aisle and flailing around in

ecstasy. Because Margery was a lay woman, a lot

of energy

was spent in determining if her fits came from God or the Devil. She visited bishops and submitted to their

examinations. Lucky for her, her experiences were authenticated by the

church. Joan of Arc was not so lucky.

These

women (and men, too) were generally called mystics,

for their religious expression was often visionary and accompanied by

many

kinds of wonders, such as levitation. But

fasting was a common thread and women and girls

who fasted often

claimed, as the desert hermits had as well, to live from spiritual food. In the case of these women, the food could

spontaneously fill their mouths in the form of blood or honeycomb. It was delivered to them by angels, saints,

the Virgin Mary, or Jesus himself.

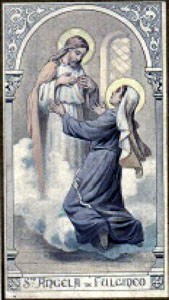

Angela of Foligno (b c.1250),

was a

nun who took

only the Eucharist while enduring long periods of

fasting. Christ as nourisher comes through

in this

image, where Christ seems to reveal his breast as

Angela receives a spiritual

food in the form of blood

(or milk?) from him. (Image from wiki

commons.)

Images

can show nuns or abbesses drinking the blood of Christ as it

oozes from the wound at his side, either into a chalice or directly

into their

mouths. In some of these images,

Christ’s wound is raised high on the chest and his action seem to

imitate lactation. Lactation (breast feeding)

was an act of deep

caring and sustenance, and though today breastfeeding can embarrass us,

we still use phrases like ‘The milk of human

kindness.’

Is this Anorexia

Nervosa?

No. The

manifestation of fasting as an extreme spiritual

practice has nothing to do with Anorexia. Today

we understand Anorexia Nervosa as a particular

kind of

disease. In the Middle Ages, things were

culturally and socially very different. People

still suffered from anxiety and depression and, no doubt, food

disorders. But there is nothing to say

that these woman and girls (and men, too) were anorexics.

Importantly, many of the girls who supposedly

ate nothing but communion were also said to look healthy and well, and

this,

you see, is also part of the miracle.

Some

researchers have likened the fasting girls of the

middle ages to girls today suffering from Anorexia. I

can see why they do, because there are no

doubt similarities. But I worry that

likening Fasting Girls to Anorexics romanticizes a terrible modern

disease and

misconstrues an ancient spiritual (if extreme) practice.

Should girls today

practice this kind of fasting?

No! Again, this

behavior comes out of a very different time and place. Girls

today shouldn’t wear corsets, either. Today we understand fasting and the body

differently than we did then. If you would like

to

undertake a fast for health or spiritual reasons, read some good books

on

modern fasting and good health, and talk to your pastor, spiritual

advisor,

dietitian, or doctor. Remember, we

understand today that the body is a beautiful expression of God’s

creation. Fasting together with good and

healthy diet

is supposed to be a healthful and beautiful thing.

Suggestions for

further reading:

If you like historical

fiction, follow my mystic nun

protagonist in The Saint and the

Fasting Girl

Find more articles and information at

my website historyfish.net

For a fascinating non-fiction tour de

force of women saints

and abbesses and other religious women read Holy Feast Holy Fast by Caroline

Walker Bynum and Forgetful of their

Sex by Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg. These

scholarly books chronicle the lives of women from the religious east

and west

who endured (or sought out) tremendous physical hardship in a quest of

extremism, seeking to live as Christ lived and to endure as Christ

endured.

I also recommend the book Memoirs of a Medieval Woman: The

Life and Times of Margery Kempe, by Lois Collins, Harper

Perennial, 1983.

Sources:

Holy Feast Holy Fast by Caroline

Walker Bynum, University of California

Press, 1988.

The Lives of the Desert Fathers

translated by Norman

Russell, Cistercian Publications,1980.

Desert Christians by William Harmless,

Oxford University

Press, 2004.

Forgetful of their Sex by Jane

Tibbetts Schulenburg, University

of Chicago Press, 1998.

The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages

by Terence Scully, Boydell

Press, 1997.

The Book of Margery Kempe, translated

by John Skinner,

Penguin Classics, 2000.

Go to the monastics

homepage on historyfish.net

|